The Fort Devens Dispatch

My first Army assignment sent me all the way down Route 2 -- to a job I loved

Here’s another excerpt from a memoir that I’m working on . . .

After my 10 weeks at Fort Harrison telling the master sergeant what to do, I was assigned to Fort Devens in Massachusetts — a one-hour drive from good old Beverly. It wasn’t a coincidence. During basic training at Fort Knox we had been given a piece of paper asking us to list our top three choices for where we would like to be stationed. Being the world traveler that I was, I picked Fort Devens as my top choice. I think I threw Hawaii in there just to make it look good, but I was homesick and unsure of myself and felt the gravitational pull of familiar Beverly. After a week of leave back home, I made the drive to Fort Devens to report for duty. My assignment was to serve as the information specialist for the 39th Engineer Battalion. When I walked into the 39th Headquarters and told the sergeant at the desk that I was reporting for duty, he took one look at me and asked a good question — Where was my uniform?

Being new at this Army stuff I had no idea I was actually supposed to be wearing my uniform when I reported for duty. Shorts and a T-shirt were apparently not part of the military dress code. The sergeant shook his head incredulously and told me to get out and not come back until I was in uniform. I got back in my car and drove around Fort Devens looking for a place to change clothes. I parked behind the sports arena, pulled my wrinkled Army fatigues and boots out of my duffel bag, got dressed and hustled back to the 39th, ready to assume my role as information specialist, the man with all the answers to all the questions, except for maybe the one about when to wear your uniform. In I walked finally looking like a soldier, albeit a wrinkled one, only to find out there had been a snafu with the paperwork, which I would eventually learn was pretty much a standard thing in the armed forces of the US of A. The sergeant said I was now assigned to Headquarters Division down the street. He shook his head in sympathy. “Headquarters Division,” he said. “That’s a bad unit.” He suggested that the soldiers in HQ weren’t really soldiers, more like a bunch of clerks and paper pushers who were just biding time and weren’t really there to defend their country on the front lines. Hmmm, I thought. Sounds like my kind of place.

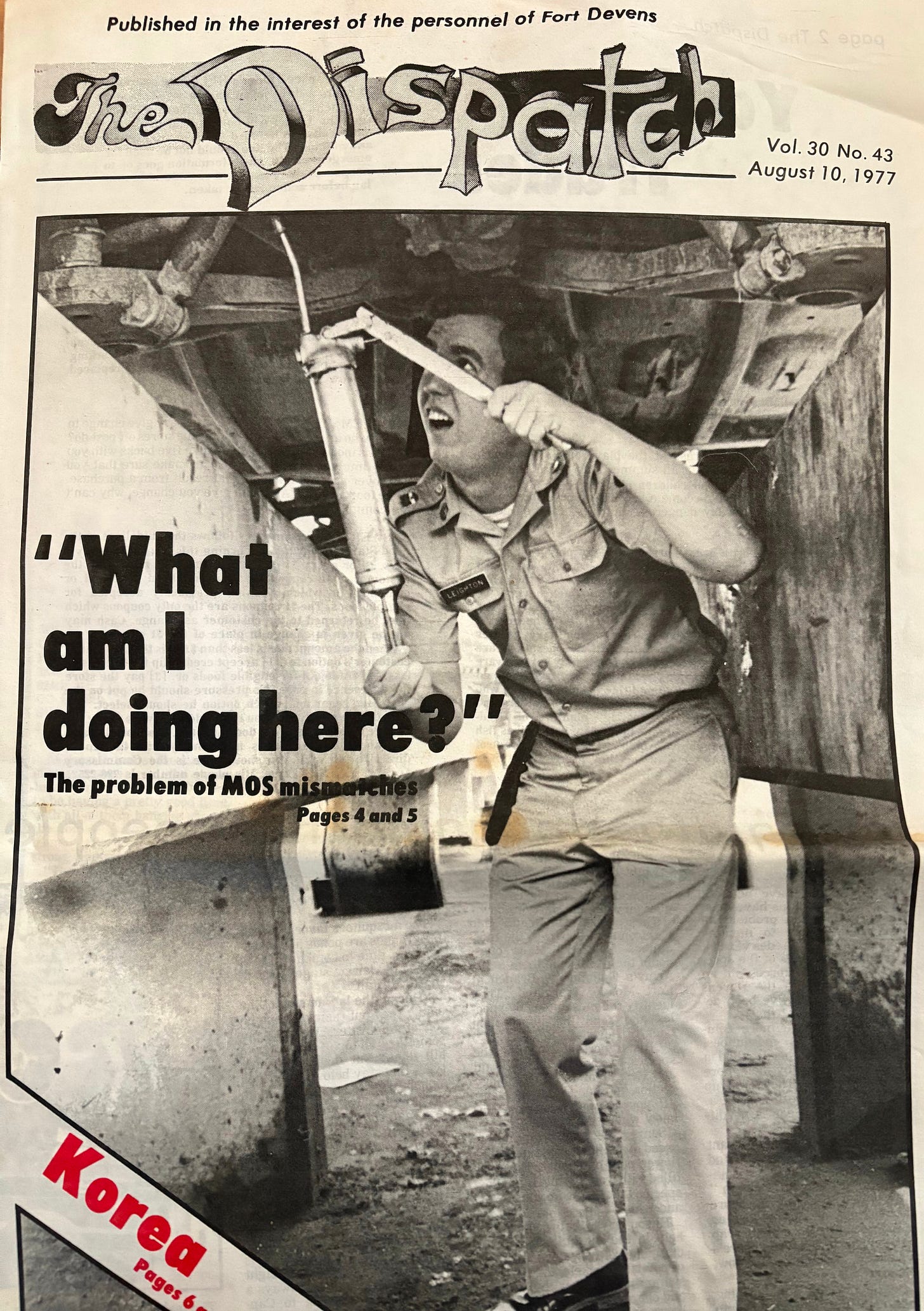

The Fort Devens Dispatch was a weekly newspaper that covered the comings and goings at Devens. The fort had started out in 1917 as Camp Devens on land in central Massachusetts that the military leased, and later purchased, from 112 owners in four different towns. When I got there in 1975 it was home to the Army Security Agency Training Center & School and the 10th Special Forces Group (Airborne). I remember walking into the Dispatch office for the first time feeling pretty confident, thinking that people were going to like me and that I was going to be a good reporter. It was a level of confidence I had never remotely approached when I was back in Beverly and slinking quietly through the halls of Beverly High. I didn’t know where it came from but I was excited to start working for the Fort Devens Dispatch and become a proud member of the raggedy-ass Headquarters Division.

My editor at The Dispatch was Sergeant Jim Price, a preternaturally bald man with glasses and definitely the friendliest sergeant I had met that day. He insisted I call him Jim and probably could not have cared less if I had walked through the doors in shorts and a T-shirt as long as I could write a story. My first assignment was to cover a golf tournament at the golf course on base. But when I got there, there was no golf tournament. Something about a paperwork snafu, I think. So I sat down with the gruff golf pro with the equally gruff name of Mac McHarg. Mac told me his life story in about 45 minutes. I went back to the office and banged out a story on the life and times of Mac McHarg on a Royal typewriter. I sat at my desk as Jim Price read the story in his cubicle in the corner. He said he loved it and praised my initiative for coming back with a story when there didn’t seem to be a story. I knew then that I loved Jim Price and I loved writing stories and I had found a home at the Fort Devens Dispatch.

For the next three years I wrote stories and wore wrinkled uniforms and drove back down Route 2 on weekends to hang out in beloved Beverly. Jim Price was a mentor and a friend who treated me like a son, even though, at 26, he was only eight years older than me. He was married with two kids and had been in the Army for six years, including a stint in Germany. He pushed us to write stories that would rile the higher-ups. One time he sent me to stand outside the Post Exchange, Devens’ big all-purpose store, to test whether superior officers would correct a soldier whose appearance was not up to snuff, as they were required to do. I guess he figured it was a natural role for me. Maybe it was because of the time General George S. Patton IV — son of the famous World War II General Patton — on a visit to Fort Devens asked Jim who was the soldier standing in the corner who looked like an “apparition.” That was me. So I went to the PX more disheveled than usual — a missing rank pin, no name tag, shirt partially untucked — and stood outside, waiting to be upbraided by various officers and NCO’s. But only a few of them bothered to say anything. We had our Page One story — a photo of sloppy-looking me below a gotcha headline saying officers were failing to enforce uniform standards. It wasn’t exactly David Halberstam reporting from the jungles of Vietnam. But it was fun and got some attention, and I loved the fact that we could get away with calling out the higher-ups for their mistakes. Even in the Army, newspapers had a power of their own. I was 18 years old and had no clue how to use that power, but I would come to learn that a good newspaper could stick up for the little guy and keep the big guys on their toes.

Thanks to Jim Price’s leadership, we ended up winning an award for best newspaper in the Army one year. I loved the job and the people I worked with. They were newspaper people, and I was a newspaper person, and it felt like that’s what I should be doing. And I never really stopped.

This will be an amazing memoir!

Really enjoying these excerpts, Paul.